by Craig Klugman, Ph.D.

When I was a graduate student learning about the job of being an academic, my advisor gave me some good advice. He told me to teach my classes, minimize my service, write everyday, and keep up with the literature. Teaching innovative classes using technology and active learning takes more time than lectures and seminars did. I became a department chair, which automatically increased my service duties. I still write, nearly everyday. What I do not have time for is keeping up with the literature. And I feel guilty about that. Instead, I read the emailed table of contents of a handful of journals and might read a couple of articles if they grab me. I skim through the two or three journals to which I subscribe. And if someone posts an interesting link on a listserv or Facebook page, I may skim it. If I’m working on a particular topic, I’ll try to find everything that has been written on that narrow thing (computers make it possible to find this information without having to “master” it). But in no way do I “keep up with the literature.” And I haven’t been able to since day one.

Yes, I feel like I am shirking my scholarly duty. And this may be one of the most hidden secrets of academics, as it seems like most of us do not keep up. In a meeting the other day, my colleagues in other disciplines mentioned that they also do not keep up with their respective literatures. Most have given up even trying. “There’s simply too much out there and it seems like everyday there’s a new journal created,” one of them said. Those confessions certainly made me feel better.

And no wonder, we can’t keep up. A recent study out of the U.K. shows that most academics (at least those they interviewed) not only do not keep up, but they do not even trust the articles they read. The problem, the researchers say, is there is simply too much new information in too many articles out there. One of the research subjects quoted in the article said:

This notion of “too much information” is known as overflow. With a shift to “publish-or-perish” evaluation of faculty, and the need for having a record of publication to get a grant or a job or even into grad school, there are simply more articles being submitted and in response, more new journals than ever before. There are still relatively few “prestigious” journals. The online realm has enabled the proliferation of many more journals such as the PLOS journals and the many pay-for-print outlets (also known as “predatory publishers”). This latter group alone accounted for 400,00 articles in 8,000 journals in 2014, according to Retraction Watch –yes, the problem is so big there is even a website dedicated to reporting on retractions. In 2010, there were only 53,000 articles in such journals.

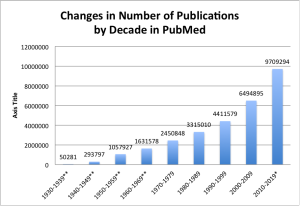

What about in more traditional publishing outlets? I took a look at PubMed and searched for the total number of articles in the database for each decade. As Figure 1 shows, there has been an exponential increase in the number of articles listed on PubMed every decade. The database is less complete before 1966 and the 2010-2015 number is a projection based on current rate of publication so far this decade (5.6 million articles through September 30, 2015). The actual number may be much greater. This analysis shows that every decade since the 1960s has seen a 25-33% increase in sheer number of articles.

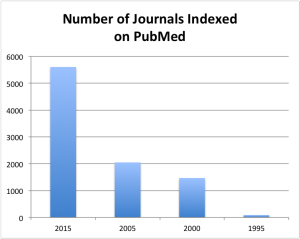

As shown in Figure 2, in 2015, there are 5,606 journals indexed in Medline. Twenty years ago, in 1995 there were 883 journals in the index. That means that 84% of current journals did not exist or were not part of PubMed only 20 years ago.

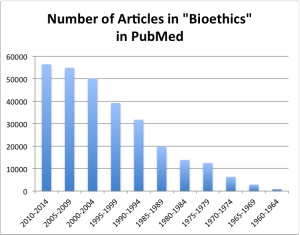

In bioethics the increase in PubMed indexed articles shows growth, though not as great as for all journals more generally (figure 3). From 2010-2014 there were 56,439 articles in the PubMed “bioethics” filter where 20 years ago, 1990-1994 saw only 39,225. This is only a 43.7% increase but still represents nearly a doubling of the number of articles published and posted on that index.

The result of assessing scholars based on quantity of productivity defined solely as the number of publications (secondly weighed against the impact factor of the journal) is that they publish more. We are smart that way—tell us on what basis we are evaluated and we will do more of the things that count. More publications means less time to analyze, conduct new research, and peer review. A study that might have been published as one article in an earlier age will now be divided into its least publishable unit which could net 2 or 3 pubs from the same dataset. Peer-reviewers have less time than ever to read critically. Of three reviewers comments of a recent article I submitted, two wrote less than 3 lines. Peer-review isn’t fulfilling its function of making sure we do good work. For example, A recent study in psychology was unable to replicate more than half of published studies.

The pressure for publication productivity could be also be the cause of the draconian increases in research errors, misconduct, and article retractions. Though the most retractions do occur in the relative handful of prestigious journals—maybe, because those are the ones most read. When you have little time for reading, then you read what is ostensibly, the best.

Something is broken with the research enterprise when even those doing research do not trust the system. Many of us chose to go into the academic life because it afforded time to dialogue with others on important issues. But the market pressures and assessment standards to which we are held accountable have the effect of forcing us to focus on churning out more papers that say less. Couple that with higher stakes in publishing and grant-getting, lack of time and energy to do real peer review, and there is a perfect storm for distrust in science. And if scholars do not trust the science in our professional journals, how can we expect the public to trust science or even to continue to fund it?

The answer is we need to publish less. We need to reform a broken system that penalizes deep thought and reflection in favor of products that can be counted, even if they are not meaningful and perhaps even wrong. When the inmates realize they are in an asylum, it’s time to turn things around.