by Craig Klugman, Ph.D.

After age 40, the risk of developing a cataract increases. By 75 years of age in the U.S.,half of whites, 53 percent of blacks and 61 percent of Latinx develop cataracts. Although rarer, children (under age 15) can also develop cataracts that results in blindness and other visual impairment. In infants, a cataract can effect brain development. Cataracts affect 0.0103% of children worldwide, which comes out to 191,000 cases annually.

Three years ago, Naturepublished a groundbreaking studythat used the eyes own stem cells to regenerate a lens rather than relying on an artificial lens replacement. Twelve infants in China with cataracts were enrolled in this experiment. Many of the scientists in this study had appointments at both UC San Diego and Sun Yat-sen University (Guangzhou, China). Their experiment reported that 100% of the 24 eyes developed perfect new lenses and at a far lower complication rate than the 24 children (48 eyes) in the control group who received a different procedure. The study has been cited 25 times.

Eighteen months after submitting their concerns, Nature published two letters by 26 doctors expressing alarm about the study. In one letter, the authors stated, “We have concerns regarding features of the presented data and the conclusions reached in the article. This has implications for our patients who ask for such surgical intervention.”The second letter said, “the early outcomes reported in the experimental group fall short of outcomes achievable through conventional treatment in this population.”Among the concerns of these international clinician-authors were: the control group did not receive the standard of care, that delays in performing the procedures (which should be in the first few months of life) may have led to permanent visual losses inthe subjects, the conclusions were not supported by the data, that the original study overstated its success, mislabeling images in the paper, using outdated tests to prove their success, “varied follow-up, poor visual acuities, insufficient details regarding adverse events, and a lack of information about the need for additional surgeries”, and unnecessary risk to the infants.

Reading the original 2016 paperis eye-opening. One of the first things I noted was that the paper included results from both animal studies and human studies in the same publication. Even more disturbing, the animal results were not very successful based on the images provided in the paper. The letters discussed above show how the images were mislabeled and do not show the great results expressed in the text. Other scientific concerns beyond mislabeling and drawing conclusions not supported by the evidence, is that the control patients did not receive the gold standard (as required under the World Medical Association) but a lesser method, and they had far worse outcomes than patients receiving standard care around the world.

Some of the critics of the study have questions the role ofNaturein this process. The original manuscript was submitted in October 2014, accepted in January 2016 and published in March 2016. Both letters were submitted in April 2016 and not published until April 2018. Perhaps the longer time for publishing the letters were related to the need to get a response from the original study authors. However, the expressed concerns are major and could affect how thousands of children are treated each year (remember those 25 citations?). Did the journal have a responsibility to publish the letters sooner? To retract or at least asterisk (question) the original study article? This line of thinking leads to the question of peer-review. If the 26 doctors from around the world were so quick to find a problem with the study paper, why didn’t peer-reviewers flag concerns? In the last few years there have been a number of articleson the problems of peer review. Among the issues is that reviewers are busy and this extra unpaid work is often not done thoroughly, that there is limited training for doing peer-review, that there are conflicts of interest (studying a similar area and thus being a competitor), bias, inconsistency in quality and depth of reviews, and a history of reviewers missing big problemswith studies. There is also a crisis with reproducibilityin that many experiments, as described in their papers, cannot be reproduced by others. Can these particular findings be replicated? A single case study in Russia published in 2017found that while the surgery took less time, the subject’s optical acuity was objectively poor (mother says it was better), with plans for follow up that have not been published. The Chinese researchers also state that they will be conducting long term follow up.

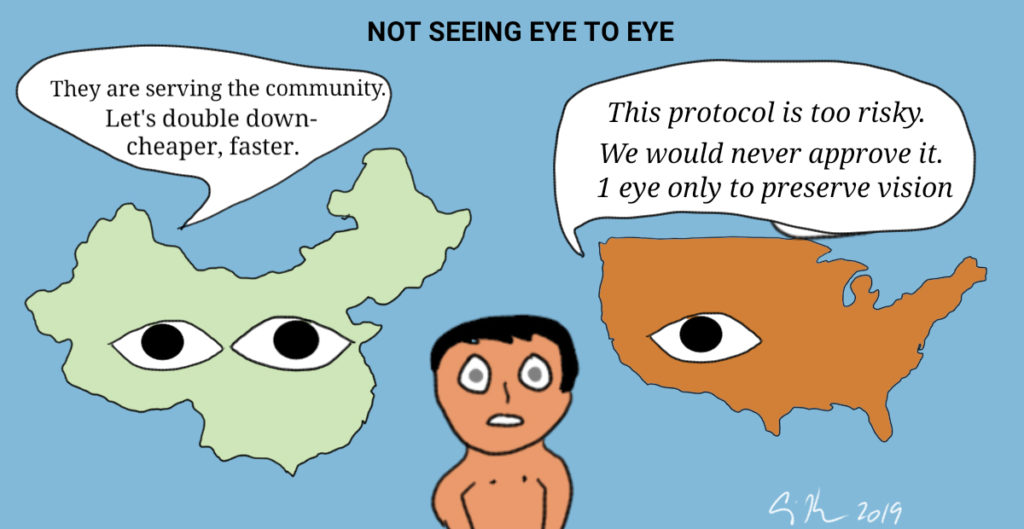

I am not a biological scientist, but my social science training in research methodology alerted me to several problems with this study. Most glaringly, I found it odd that while there were 12 experimental subjects (24 eyes) there were 24 control subjects (48 eyes). Why was the control group twice as large? Were there more in the experimental group but their results were less than perfect, so they were removed? Did subjects drop out and if so, why? Were the researchers unable to get parental consent for more than 12 experimental subjects? Many important questions remain unanswered. Note that for the subjects, both eyes received the same treatment. Allegedly this was to be help in visual development, but critics of these studies believe it was unethical to subjects to having both eyes experimented upon at the same time. In the U.S. and Europe, the standard would have been to experiment in one eye, thus increasing the likelihood for some remaining sight if the experiment does not succeed. Was experimenting on both eyes an undue risk? Did it throw the risk/benefit ratio off to the point where the study should not have been approved? Why did parents consent to having both eyes experimented on? China has developed institutional review boards and consent documents because Western scientific journals require reporting of these steps. What is not known is how carefully these reviews are done and how in depth they are conducted. In the U.S., IRBs exist because of a federal law to protect human subjects. In a culture whose philosophy is based on the community rather than the individual, asking for informed consent may not have meaning because there might not be a cultural understanding of saying “no” in an authoritarian state and one with a history of the individual being subsumed under the collective.

Why did these scientists with U.S. university appointments do their work in China rather than the U.S.? While there could be legitimate reasons such as funding, equipment, or locations of colleagues, the answer seems to be that the work may not have been approved by a U.S.IRB. The authors’ others reasons for doing the study in China including trying to “keep the costs low” and because the work could be done in less time. China is competing heavily in medical and biological research and researchers there are pushing the bar on ethical research such as the birth of girls from edited embryos last year.

There are some cultural and philosophical differences in regards to the individual and service to the community that can account for why some research unapprovable in the U.S. is approvable in China. But the human subjects reviews should consider minimizing harm to patient (experimenting on two eyes) and need to be based on best practices of clinical trials. At the very least, an investigation into this experiment is necessary. As I am putting together my Fall quarter research ethics course, I plan to discuss this case on day one to show students that we need to study human subjects research not so that we know about what was done in the past, but so we can avoid what continues to be done today.