by Craig Klugman, Ph.D.

One of the most powerful tools that epidemiologists have for containing an outbreak is contact tracing—finding out all of the people with whom an infected person has had contact during the period when they were potentially shedding the virus. The identified individuals will then be placed under isolation and observed for symptoms. This method has been used in this outbreak when public health authorities recommend isolation for people who have been near someone who is infected or have traveled from a region with a high number of cases. The idea is that by creating a cordon around people who were infected and potentially infected, they cannot spread the infection further: The outbreak is contained. Of course, this approach requires being able to identify contacts, having testing available, adhering to the isolation, and knowing how the virus spreads.

Contact tracing is one of the most challenging exercises in an age where people can travel to most parts of the planet in less than 24 hours. In a given day, we may travel from home and to work via public transit. We may visit a restaurant for lunch, cleaners, and a grocery store. Thus, a carrier could be infecting people in all of these places. Contact tracing means identifying everyone on that plane (or bus or subway), everyone who was in your office, in your home, at the restaurant, dry cleaners, and grocery store. The job is enormous and very difficult. Social distancing simplifies things because we aren’t out and about.

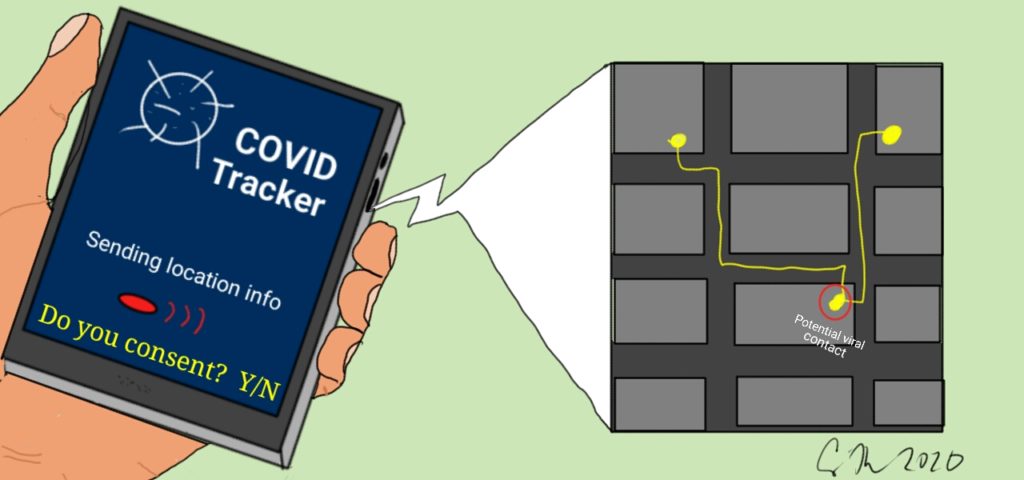

Still, tracing is necessary. One proposal for how to track people is to use the ubiquitous cell phone—a device that knows approximately where you are based on GPS and connecting to the nearest tower. Thus, one could potentially know who was in a particular area when a COVID-19 carrier was there. China (and Taiwan), Iran, Israel, and South Korea are using cell phone tracking in tracing contacts and trying to contain the epidemic.

In the U.S., Facebook has started sharing its location data with researchers (such as Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health) to study the virus’s spread. This shared data has been anonymized, meaning identifying information has been stripped. Researchers can see where people gathered and create viral genealogical trees of infection, but they can’t see names, phone numbers, or IMEI codes and they can’t inform those people that they may have come into contact with a COVID patient.

What if the identifying information was kept intact: Could a public health department send a message to people whose phones marked them as being in a certain location at the same time as someone infected with COVID-19? This way as soon as person’s positive status was confirmed, the geolocation information would allow very fast identification and isolation of contacts. Not all of those people will have been infected, but they could all have potentially been infected.

According to the U.S. Supreme Court, privacy means that your geolocation data can only be taken and used with your permission or with a court order. Cell phone privacy is stricter here than in many other nations. Even if the court order is given, the cell phone provider, device manufacture, or even app developer might be reluctant to share information. Much cell phone data is encrypted and companies are reluctant to give law enforcement (or in this case, public health authorities) the encryptions keys: A company may not want to risk trust with their customers by sharing this information. Besides violating privacy, automatic sharing programs would undermine autonomy and the idea that a person should be able to consent whether to be tracked or have their information shared. Thus, another proposal is to create an opt-in program where people could choose to share their data with public health departments through their cell phone carriers. This would align more with American individualism and focus on consenting to share information. Another approach would allow people to download an app that would separately log your location information and could be accessible by public health authorities as part of the permissions—another version of opt-in.

In more communally-oriented cultures, the idea of giving personal information to benefit the greater population is expected. But in the U.S, the notion of individual self-governance and personal privacy is strong. We preference the individual over the community. Thus, requests of the government to require or demand cell phone data is likely to be met with resistance. An opt-in program, while not giving us much data, would give some idea of where contacts may have occurred. This approach balances our sense of personal privacy with the needs of public health authorities to protect the community’s health.

The question then is how much should we relinquish our civil right to privacy in an effort to stop the pandemic? And if we did allow collecting of (unconsented) data, would we be able to close that door once the epidemic is past?